From sexy heels trussed and presented on a silver platter to Damien Hirst's formaldehyde shark, a tour through some of the strangest, most shocking surrealist art around

Salvador Dalí's Lobster Telephone, the ultimate 'surrealist object' at the Pompidou Centre in 2002. Photograph: Jean-Pierre Muller/EPA

Salvador Dalí, Lobster Telephone (1936)

The surrealist movement in the 1920s and 30s believed that revolutions begin in dreams. Taking their inspiration partly from the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, they set out to create art from the unconscious. Dalí's Lobster Telephone is an iconic example of one of their most haunting discoveries, the "surrealist object", a ready-made thing or combination of things that speaks in some obsessive, inexplicable way to the artist. For Dalí, telephones are sinister messengers from "Beyond" while the lobster is sexual. With a lobster telephone, you can dial up a dream.

Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991)

The surrealist object lives on, as a shark preserved in formaldehyde and appearing to swim relentlessly through the white space of an art gallery. There is only one word for Damien Hirst's toothy tiger shark, which gapes as it appears to glide towards you, as this natural history specimen is given the illusion of movement by the refractive perspectives of a glass vitrine: surreal. With its gradual wrinkling and decay, the shark has become even more bizarrely surrealist.

The Colossus of Constantine (4th century)

Big and bizarre … the 4th-century bust of Emperor Constantine, in Rome. Photograph: Eye Ubiquitous/Rex

Big and bizarre … the 4th-century bust of Emperor Constantine, in Rome. Photograph: Eye Ubiquitous/Rex

The gigantic remains of a statue of Emperor Constantine, preserved in Rome's Capitoline Museum, have haunted the dreams of artists for centuries. In the 18th century, Henry Fuseli portrayed an artist "overwhelmed" by the strange spectacle of Constantine's enormous marble hand. In the 1950s, artist Robert Rauschenberg photographed his companion Cy Twombly standing by the same gargantuan relics. The sheer scale of this statue dwarfs reason; its fragments are utterly surreal.

Joan Miró, Object (1936)

The Catalan visionary Joan Miró created a quintessential surrealist object when he joined together a pirate's bizarre hoard, including a parrot, a woman's stockinged leg, a map, a hat and a swinging ball. Hisconstellation of dream images found in everyday life creates a sense of magic and mystery that opens the mind.

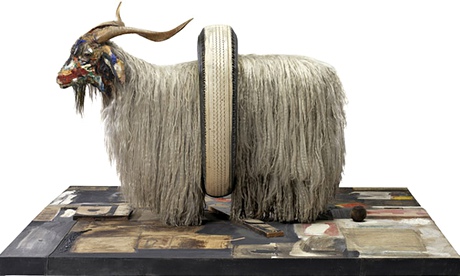

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram (1955-59)

Stuffed … Robert Rauschenberg's 1963 sculpture Monogram. Photograph: Moderna Museet/Prallan Allsten

Stuffed … Robert Rauschenberg's 1963 sculpture Monogram. Photograph: Moderna Museet/Prallan Allsten

When Robert Rauschenberg found a stuffed goat while trawling New York dumps and antique shops, he could hardly ignore the sexual charge of its phallic horns and mythological associations: In ancient Greece goat-legged satyrs chased nymphs across the hillsides; in Christian art the devil himself is goatish. Rausenberg completed this work by thrusting the goat through a tyre, as in some cosmic sex act. The result is one of the strangest and most memorable of all readymades.

Méret Oppenheim, My Nurse (1936)

The surrealist Méret Oppenheim had an eye for presenting suggestive stuff from the world around us. She famously, for instance, covered a cup and saucer with fur to create an image of oral pleasure. Sex and food are similarly mingled in My Nurse. Oppenheim presents a pair of white high-heeled shoes, trussed and presented on a silver platter like a delicious meal for a fetishist.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Song of Love (1914)

Arguably, the first surrealist objects appeared in the paintings of melancholy modern spaces and enigmatic relics that Giorgio de Chirico was making on the eve of the first world war. In The Song of Love, a rubber glove hangs incongruously next to a marble head. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire – who coined the word surreal – recorded de Chirico going out and buying this very rubber glove. In other words, it is not just a painted fantasy but also a surreal object from the real world.

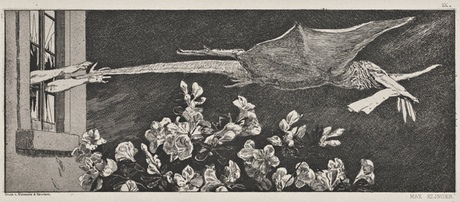

Max Klinger, A Glove (1881-1898)

Outlandish … a print from Max Klinger's 1881 series A Glove

Outlandish … a print from Max Klinger's 1881 series A Glove

In this astonishing series of late 19th-century prints a man – the artist – sees that a woman has dropped her glove. In a series of increasingly outlandish fantasies he pours his passion and longing for the unknown woman into an intense relationship with her glove. Klinger's masterpiece proves that many surrealist ideas, including its cult of obsessional objects, were anticipated in the age of fin de siècle decadence.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Louise Bourgeois (1982)

In this beguiling photograph, the suggestively smiling Louis Bourgeois holds a truly surreal object, one of her provocatively carnal sculptures whose phallic form is richly emphasised by Mapplethorpe's black and white photograph. In her long creative life, Bourgeois directly linked the age of surrealism with our own time. This picture conveys the surreal charge of the woman and her works.

Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915)

Before the surrealists were possessed by objects they found at Paris flea markets, Marcel Duchamp "selected" his readymades. The difference between a Duchampian readymade and a surrealist object is the difference between Duchamp's sly irony and Dalí's ecstatic obsessions. Duchamp's objects, however, evoke the same irrational forces that were to loom large in surrealism. This 1915 readymade consists of a snow shovel and a title that warns of imminent injury: Whose arm is about to be broken? Is it mine? This shovel is a humorous portent.

0 comments:

Post a Comment